What It Means To Be “Too Early”

“Too Early”. Venture firms tell founders every day for one reason or another that the company is “too early” for consideration, but to please, come back when you’re ready and we can evaluate then.

“Too Early”. Venture firms tell founders every day for one reason or another that the company is “too early” for consideration, but to please, come back when you’re ready and we can evaluate then.

It’s also not the reason they’re not investing.

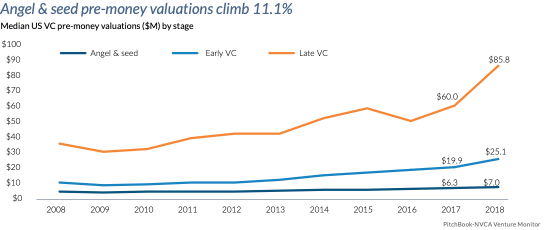

As an investor, being “Early” typically means you can invest at the lowest entry point, maximizing your potential returns. If investing early can maximize returns, can an investment really ever be TOO early?

“We think this will be a great investment, however if we invested in it today, our rate of return would be too great — and we are not equipped to deliver those kind of returns to our limited partners”

— said no-one ever.

Investments fail because of a poor thesis, an inability to execute, a fracturing of the leadership team, a competitive threat, or literally dozens of other reasons (compiled very well here).

When you’re “too early”, it either means best case that the company hasn’t generated enough data points for that VC to validate an investment thesis, or worst case, they believe one of the aforementioned reasons (poor thesis, leadership, competition) will ultimately be your downfall and they’re unwilling to tell you.

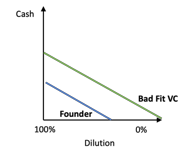

Assuming best case, this may be due to the fact that the company hasn’t been around all that long — and doesn’t actually have any data to provide (ie the “this is our idea for a company will you fund it” pitch). More likely though, the “too early” rationale is validated by the fact the VC firm is not equipped or experienced to help a company at your size.

Using simple math, a VC firm with $1BN under management and 3 general partners likely does not have the ability to dedicate general partner time to help a company where they’ve made an investment of $500,000 succeed. Therefore, if you’re not equipped to spend the kind of money that VC firm needs to invest to justify the general partner’s time and oversight, then that company is truly “Too Early” for that fund.

At Tuhaye, we invest pre-seed. We’re the first investors in a business, meaning companies are never “Too Early”. That doesn’t mean we’ll always invest (to the contrary, we’ve invested in less than 0.1% of all businesses we’ve seen since 2016).

When we’re evaluating companies, we seek to answer two critical questions.

• • •

1) Can money unlock growth at the company?

2) Do we have an expertise that can help unlock additional growth at the company?

• • •

Since the second question is specific to our firm’s sector focus on enterprise software, I’ll simply focus on the first question, which is more or less easy to evaluate.

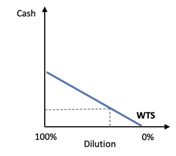

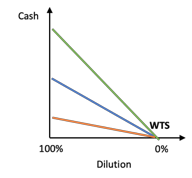

With most startups, money solves only one problem: extending the date at which you run out of money. To invest successfully at the early stage, you need to identify companies where cash does not simply extend the runway, you seek out businesses where the constraining factor on growth IS a lack of money.

In practice, this is the MVP that has had successful sales to date, but where it’s clear that by investing in additional product engineering resources, the company can expand the market to which it sells its product. It’s the company with excellent unit economics around sales but is under-resourced to hire faster.

Whatever the case is, the deeper issue is that if money isn’t solving a constraint factor around growth, then it’s usually causing another one: the company is not growing fast enough to meet the investor expectations.

So what’s the best way to avoid the brand of “Too Early”? We’ll share a framework in an upcoming post specifically about what we feel makes a strong pitch — but the above all else, make the case that it’s the money that’s going to make this successful. You’ve pulled every available lever you can pull to this point to help the company grow to this point, now you need a balance sheet to be able to do that much more.

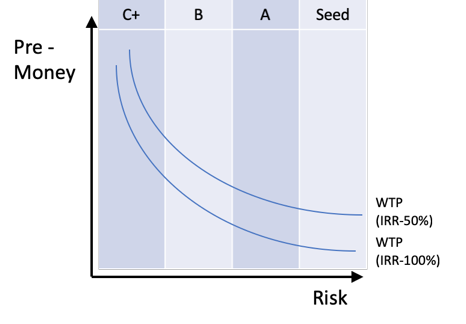

Of course in the venture capital business, Risk is extremely difficult to measure, which is why so many funds return very little capital and other funds consistently outperform benchmarks — and why so many founders have strained relationships with their investors.

Of course in the venture capital business, Risk is extremely difficult to measure, which is why so many funds return very little capital and other funds consistently outperform benchmarks — and why so many founders have strained relationships with their investors.