Valuation Theory and the Flawed Premise of “Pre-Money” Valuation

Since the start of the “unicorn” era, investors, founders, and journalists have all focused on private valuations. Using valuations, markets characterize startups as being either “cheap” or “rich” relative to their size and stage on the relentless slog toward $1 billion.

In order to reach these heights, startups typically raise outside capital from VCs in exchange for an ownership stake in the business. This process creates a valuation for the fully financed business, often referred to as the “Post-Money.” Subtracting the cash invested, this imputes a “Pre-Money” valuation that characterizes the value of a business prior to investment.

But what does a pre-money valuation for a seed-stage business even mean? How can an exceptional team with mere wireframes and intangible indicators of market demand be worth $5M in itself? How can a company that doesn’t have the necessary capital on hand to realize it’s vision be worth anything prior to raising that money?

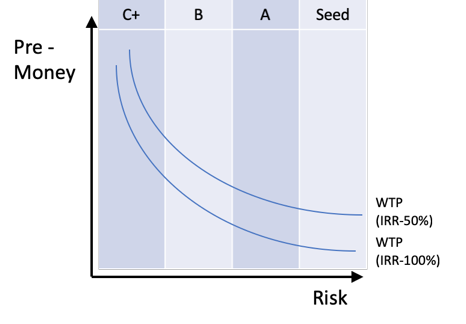

The answer is simply that a company is never worth its venture-backed valuation. The valuation is a reflection of the investor’s perception of the underlying risk of the investment. The greater the risk, the lower the valuation an investor is willing to pay in order to achieve their desired rate of return.

It would then follow that investors seeking greater rates of return would only be willing to invest in businesses at lower valuations that have the same overall risk profile of similar businesses pricing at higher levels.

Important Note: Funds targeting extremely high IRRs typically can’t offset the high amount of Risk associated with each investment, leading to outlier fund performance in both positive and negative instances.

The independent variable here is Risk. Risk is not the measurement of whether a company will succeed or fail, but rather the probability of the company reaching a defined successful outcome. If investors can perfectly measure Risk, then they will perfectly price investments to achieve a target rate-of-return across a full portfolio. This would create an environmental equilibrium where a founders’ willingness to take on dilution matches an investors’ willingness to take on risk. Comparing two valuations of separate businesses is, therefore, comparing apples and oranges; it only reflects the risk appetites of the investors and founders in each deal.

Of course in the venture capital business, Risk is extremely difficult to measure, which is why so many funds return very little capital and other funds consistently outperform benchmarks — and why so many founders have strained relationships with their investors.

Of course in the venture capital business, Risk is extremely difficult to measure, which is why so many funds return very little capital and other funds consistently outperform benchmarks — and why so many founders have strained relationships with their investors.

Some investors are simply better at understanding and pricing risk than others.

Here are a few ways that some investors navigate the pricing of Risk:

- They are thesis or sector-focused: VC’s investing in specific researched verticals of expertise, better-quantified Risk by through an understanding of the long-term value of the industry (ex. Union Square Ventures, Lux Capital)

- They are stage-focused: VC’s investing in specific sized companies, better-quantifying Risk through an understanding of the challenges faced by businesses of that size, regardless of sector (ex. First Round Capital)

- They engrain Value-add into their operations: VC’s with additional resources and platform support that are able to de-risk an investment through providing time and services at an additional cost beyond the impact of cash and self-management (ex. a16z).

- Incubation: VC’s who start businesses themselves either through the GP or through EIRs, reducing risk associated with investing in an unknown team (ex. Alleycorp).

In conversation, these strategies are often answers to the question, how do you differentiate? However, in practice, they are tactics used by investors to measure Risk.

The pre-money valuation is reflective of the investors’ calculated perception of Risk, not the asset value of the business. However, through correctly identifying this Risk, venture firms are able to drive outsized returns, regardless of the valuation they pay. Investors, founders, and journalists should remind themselves of these variables when comparing valuations across businesses.

Now let’s get tactical. To see how Risk can be evaluated in a company’s valuation, click here for Part II.